DARK

INTRIGUES

DARK

INTRIGUES

IN SCENIC PLACES by Antares

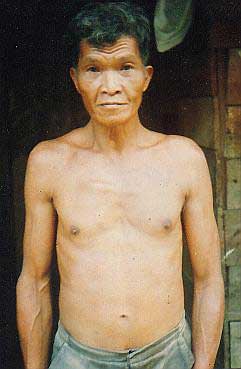

As the solstice sun began to sink behind the misty hills of Pertak on June 22, a wild-eyed Rafik Benut staggered towards Lot 22, Kampung Pertak, brandishing a bunch of keys and a parang. No one made an attempt to stop him as he let himself into the house after a bit of fumbling with the keys. Even the dogs gave him a wide berth. Rafik was well-known for his violent outbursts, especially when intoxicated.

About three years ago, Rafik had suddenly reappeared in the village, having served a 6-year jail sentence for chopping up the headman’s 19-year-old daughter and attempting to burn the gory evidence. The headman, Bidar Chik, asked that Rafik be relocated to another community but the JHEOA (Orang Asli Affairs Department) overrode his protests. Rafik was a reformed man, they asserted, and furthermore had converted to Islam while in prison.*

For months he had been coveting this house, which belonged to his uncle Selindar Babot (who was involved in the love triangle with Rafik and Bidar’s daughter which ended in bloodshed and grief). Selindar shared the house with two other old bachelors – Utat and Uja – but all three preferred to live 40 minutes away in a rundown shanty overlooking the river. Since they weren’t comfortable in the new 3-bedroom chalet-style house built by the dam consortium as part of the resettlement scheme, the old men had agreed to let some friends from KL use it as a weekend retreat – in exchange for a monthly food allowance of RM100 each. All parties were happy with this arrangement – except for a particular faction in the village who had been groomed to serve as the eyes and ears of the JHEOA.

When the Selangor Dam project was announced in late 1998, Bidar Chik had been outspoken in his criticism. He openly supported the No-Dam campaign, much to the consternation of the JHEOA. Eventually, Bida was pacified and “turned around” with generous presents and veiled threats by agents of the dam consortium – but he was now regarded as an uncooperative party by the JHEOA which began to cultivate a special relationship with Bidar’s deputy, Uha Anak Penengah.

A once quiet and unassuming man, Uha soon turned into a different personality. With the JHEOA behind him, Uha acquired an aura of self-importance and de facto leadership of a group of disgruntled young men with no strong ties to tradition and few hopes for the future. Some of them once had jobs with the dam consortium, driving trucks or operating excavators. Others are grass cutters with private contractors and harvest bamboo or petai on the side. But most of them spend the better part of their wages at the local liquor store – and on motorbike repairs each time they fall off their machines after a binge, which is more often than not.

Uha’s popularity among the disenchanted youth of Kg Pertak was further enhanced when he bought some musical instruments and turned his bachelor pad into a rehearsal space for the village combo. He himself learnt how to play drums fairly well, and on weekends the boom and thud of bass and drums would carry on till nearly dawn. Uha had had little luck finding himself a wife (he was married to a girl from Pahang for less than a week before she died suddenly and mysteriously) and, at 45, looked likely to join the Kg Pertak Old Bachelors’ Club.

Rumours were rife that Uha had set his romantic sights on Apin, one of the village belles, even offering her parents a large sum of money for her hand. But Apin favoured the attentions of an “outsider” – a young man from KL who had been visiting Pertak regularly for years – and who was lodging for a while at Lot 22 (Selindar, Utat and Uja’s house). Uja, before he died in March, had adopted this young man as his son.

Village legend has it that Uha’s deceased father Penengah had been rather truculent and troublesome in his day, causing inter-familial feuds that endured long after his passing. Indeed, the truculent gene seems to have been passed down to many of his sons and grandsons.

In March 1999 Ramsit Anggong, the headman of Kg Gerachi, lodged a police report against Uha and a few of his nephews for bashing him up so badly he needed to be hospitalized for five days.

No action was ever taken against the Pertak rowdies – and soon afterwards Ramsit buckled under pressure and signed over his ancestral lands to the dam project for a hefty cash compensation (more than a million, some say) and membership in the Kuala Kubu Baru Golf Club.

SHADOW HEADMAN

By the time Kg Pertak was relocated and the villagers handed the keys to their brand new brick houses with electricity and running water, Bidar Chik had virtually been bypassed by the JHEOA, whose officers preferred to deal with their hand-picked shadow headman Uha Anak Penengah - a willing accomplice to the Orang Asli Affairs Department’s agenda of maintaining their 50-year control of all Orang Asli tribes in the Malay Peninsula.

There were initial problems arising from the allocation of houses. Uha was given a house to share with his younger brother Ayul – but they weren’t on the best of terms. Ayul decided to clear an area upstream of the village to build his own plank house. Bidar claimed that spot as part of his tanah pusaka (ancestral land) and tried to stop Ayul from proceeding, whereupon Ayul’s Indonesian friends bound Bidar to a tree and threatened him with a chainsaw. Bida reported to the police and they paid a visit to Ayul’s encampment but found no one around, so they left it at that.

Bidar has understandably been keeping a low profile in the village, acutely aware that he was now headman in name only. One of the women wanted to open a café and small provision shop in Kg Pertak and decided the ideal location would be on the edge of the soccer field, near a popular picnic spot. Bidar was briefed on the plan and expressed his support. However, he said he would first have to consult the JHEOA on the matter as he had no power to give the go-ahead. The JHEOA declared that the project had potential but didn’t think the location was suitable. With that, a rare show of entrepreneurial initiative by an Orang Asli was prematurely nipped in the bud.

After 50 years of being colonized in their own homeland, most Orang Asli are incapable of pushing for what they want, believing there will always be someone in authority with the power to stop them.

And no one can blame them for feeling that way, since the JHEOA has become accustomed to treating their legal wards like one would a problematic stepchild.

Rafik Benut’s attempt to claim Lot 22, as it transpired, was instigated by Uha Anak Penengah, with the tacit endorsement of the JHEOA (or, at least, its agents in the Kuala Kubu Baru office). During a chat with two senior JHEOA officers, it became clear that they weren’t happy about Selindar and his friends continuing to live in the forest, following the old ways. If they chose to let out their property to “outsiders” the Department would hand the house over to their “Muslim convert,” a convicted killer on parole with a history of drunken brawling. Never mind if that would mean an abrupt loss of regular income for the old men. The residents of Kg Pertak wouldn’t know, anyway, that the JHEOA has no legal authority to confiscate property from Orang Asli they deem “uncooperative” to pass on to their own “willing stooges.”

In any case, how did an ex-convict and murderer acquire the keys to Lot 22? The JHEOA agents had handed a spare set to Uha, their “mainman” in Kg Pertak, who then passed the keys to his hatchet man and protégé, Rafik Benut. Ironically, these are the men entrusted by the JHEOA with maintaining village security.

And what did the official headman have to say about this entire affair? Bidar Chik was disturbed that not only was Rafik still at large in Kg Pertak and plaguing his peace of mind, but that the JHEOA had heavy-handedly overridden his authority and lent official support to one of Uha’s hooligans, instigating him to commit unlawful entry into another’s property. But Bidar was at a complete loss as to what he could do to restore order to his village. “Maybe you could invite the press here?” he suggested. “I want the world to know that hoodlums are intimidating the peace-loving folk of Kg Pertak.”

Rafik and some of Uha’s gang have repeatedly harassed Selindar and Utat for the house keys until the old men were paralyzed with fear and unable to speak their feelings. They have no desire to let Rafik seize the house from them and deprive them of a regular cash income, but want Bidar to resolve the issue on their behalf. Will the meek inherit the Earth?

I’m often asked by well-wishers what they can do to help the Orang Asli. Some offer to donate clothes, foodstuff, books, toys. Others are eager to conduct educational workshops with the kids or sponsor intercultural exchanges. A few are keen to raise funds for projects that could benefit the Orang Asli. It’s actually quite amazing how many urbanites in recent years have suddenly become aware of their brethren in “remote” areas and sincerely desire to contribute positively to the future of our Orang Asli communities.

Every little effort helps, I say, it’s always reassuring to know that one has so many friends out there. But the greatest stumbling block to the Orang Asli ever regaining the self-esteem and self-confidence, without which they are unlikely to ever regain their self-reliance, is the government department set up in 1954 to “manage their affairs” - and which continues to do so today when no legal or political justification exists, nor does a “communist threat.”

“You wouldn’t know what it’s like to be Orang Asli,” I tell them, “until

you’ve lived under the ‘benign’ despotism of the Jabatan Hal Ehwal Orang

Asli for a few generations.”

|

*14 November 2005 Update:

More than two years have passed since I wrote this report and there have been significant shifts in the general morale in Kg Pertak. For a start, the generations-old feud between Penengah's clan and the Batin's clan seems to have lost its charge and the entire village is a great deal more mellow and relaxed. A contributing factor to the newfound peace may well be the 'Bamboo Palace' project inaugurated in February 2005 when I commissioned Hitam Anak Hitap (better known as Yam Kokok) to build a thatch-roofed hut behind #21 Kg Pertak, to be used as a guesthouse. Yam Kokok is married to one of Penengah's daughters. When construction began, Yam Kokok recruited several of his relatives to help gather and weave the bertam leaves for the massive roof. Indeed, a good cross-section of the various clans ended up on the payroll for the 'Bamboo Palace' project. In the three months it took to complete, I noticed that tensions began to ease as work progressed on the hut. Being given the chance to construct a traditional style hut, which requires intensive labour and cooperation, seemed to have a therapeutic effect on everybody who contributed energy to the project. In the end, exactly half the overall construction budget of RM8,000 went towards labour - and even the youngsters who helped carry materials were paid in cash as well as in food and drinks. Indeed, the biggest shift of all occurred late one night several months ago, when Ayul, younger brother of Uha, came to visit me unexpectedly. He was completely sloshed but apparently needed someone to converse with, so I invited him up and offered him a hot coffee. Ayul told me a lot of stories about various characters in the village, but what struck me hardest was when he stated that Rafik had been wrongfully imprisoned for a crime he didn't commit. When I questioned him further on this, Ayul merely said that Rafik has been his housemate for a few years now and has no need to hide the truth from him. Weeks later, I heard Rafik yelling at my dogs and complaining that he had been bitten. I went down to investigate and saw that there was just a small tooth mark on his ankle where one of my dogs had nipped him. The skin wasn't even broken but Rafik made a huge fuss and demanded RM20 cash compensation. I gave him a blast of energetic healing, then went back to the house and returned with RM10, which Rafik accepted with delight and gratitude. This simple event shifted his formerly hostile attitude towards me. Early in November, I saw Rafik waiting for the bus to town and offered him a lift. It was the first time he had sat in my van. I turned around and asked him point blank: "Did you kill the Batin's daughter?" - adding, "Look, you were found guilty and sent to jail for six years, so it makes no difference to you - but it makes a difference to me. I want to know straight from you what the truth is." "Aku sumpah," Rafik said, "I swear I didn't do it." So why did he let his uncle Selindar off the hook? He refused to discuss it further, saying it was all in the past. Before he got off opposite the Kuala Kubu Baru Post Office, I shook Rafik's hand and apologized to him for having believed all these years that he was indeed a murderer - and for describing him as such. What was recorded in July 2003 stands as a document of the situation THEN. However, it's absolutely essential to set the record STRAIGHT. Antares

~^@^~ |

Text & Pix © Antares