"Bye, Terence, see you again!"

WHAT CAUSED self-reflective consciousness in our primate ancestors?

What was the catalyst for language, imagination, conceptual thought and

reason? Scientists, philosophers and academics posit various theories, but

few more radical than that of ethnobotanist and self-styled "psychonaut"

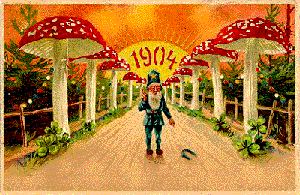

Terence McKenna .McKenna claimed that human self-awareness is the result of psychedelic

serendipity. His 1992 book Food of the Gods argues that the accidental

ingestion of psilocybin mushrooms triggered sentience in foraging,

omnivorous apes and led them - us - to put rockets on the moon in the

evolutionary wink of an eye.So-called "magic" mushrooms and their chemical relative DMT, he insisted,

are not drugs in the common sense but consciousness- expanding tools. It

is our moral duty to utilise them, he believed, in order to bootstrap

ourselves ever further up the evolutionary ladder. "Stronger doses, more

often," was the mantra that led to him being tagged the "Timothy Leary of

the Nineties" - allegedly by Timothy Leary himself.He extended his theories about psychoactive substances and their

influence on culture and society in his follow-up book, The Archaic Revival

(1992). But perhaps he was at his most convincing - and entertaining -

during the informal lectures that he gave in private homes, and the

chill-out rooms of rave clubs, on his occasional visits to Britain.

A charming, playful and exceptionally erudite raconteur, his epic

discourses on the history of psychedelic evolution - he could talk for hours

without notes, never repeating himself or exhausting his line of argument

- were peppered with amusing anecdotes, classical quotations and a nice

line in self-deprecation."I am very uncomfortable with my position in the New Age," he once

stated. "I hate all that stuff - the quartz crystal suppositories and the

channelling of dead Egyptians - it's just an affront to the thinking mind."

Yet his wry humour could also disarm all but the most bitter sceptics. "Is

DMT dangerous?" he once asked rhetorically. "Well, only if you can die of

astonishment."McKenna asserted that marijuana, DMT and psilocybin, as naturally-

occuring vegetal compounds with a long history of use by shamanic tribal

cultures, were safe for human consumption. However the nature of his

death - suddenly, relatively young, and from glioblastoma multiforma, a

rare form of cerebral cancer - will hardly further his cause. After a brain

seizure last May, doctors discovered that he had a malignant tumour.Following chemical and radiation therapy he underwent brain surgery at

the end of last year and despite an initial improvement, suffered a rapid

relapse. From the outset he was open about his condition, his website

featuring typically offhand updates: "This is a mad and wild adventure at

the fractal edge of life and death and space and time," he wrote last

summer. "Just where we love to be, right, shipmates?"Born in 1946 and raised as a Catholic in the Colorado cattle town of

Paonia, McKenna spent much of his youth memorising passages of James

Joyce and studying Carl Jung, in particular Psychology and Alchemy

(1953). He said that his first encounter with psychedelic thought was,

"looking at Colorado and trying to understand that it was once the shores

of an ocean with hundred-foot-long sauropods tromping through the

mangrove swamps".After moving to Los Altos, California, he settled in San Francisco in 1965

just as the Flower Power movement was beginning to emerge in Haight-

Ashbury. Perhaps unsurprisingly, it was here that he first tried cannabis

and LSD. Subsequently he attended UC Berkeley for two years and

travelled extensively through Asia, Europe and South America before

completing his self-tailored degree in ecology and shamanism in 1975.

After graduating he initially made his living dealing in Asian art.

However, it was during a trip to the Amazon jungle in 1971 that he and

his brother Dennis, a research pharmacologist, first encountered magic

mushrooms and DMT - the drug that McKenna would later describe as a

"megatonnage hallucinogen" and which would shape the rest of his life.The brothers brought their South American treasure home with them, and

began to cultivate psilocybin mushrooms and spread their mycological

gospel. In 1975, they published their first book, The Invisible Landscape:

mind, hallucinogens and the I Ching, and by the 1980s were growing 70

pounds of fungi every six weeks.They stopped following a friend's arrest, but by this time McKenna had

begun a new career, lecturing New Agers and old hippies on shamanic

drug use. By the early Nineties he had achieved celebrity with the rave

generation and the so-called psychedelic underground, inspiring the

chart-topping group the Shamen, who used his voice on their early

recordings and sponsored some of his visits to the UK.McKenna met and married Kathleen Harrison in the mid-1970s, and after

settling near San Francisco they had a son, Finn, and a daughter, Klea.

After divorcing in 1992, McKenna moved to Hawaii, where he founded

Botanical Dimensions, a non-profit organisation dedicated to the

investigation of "ethnomedical" and sacred plants. He also established a

gene bank of rare species near his home - a modernist house with a huge

antenna dish. When he fell ill, McKenna had started a new life with his

partner Christy Silness, whom he had met at an ethnobotanical conference

in Mexico."My real function was to give people permission," he said in his last

interview, which will appear in the May issue of Wired magazine.

"Essentially, what I existed for was to say, `Go ahead, you'll live through

it, get loaded, you don't have to be afraid.'"

(Terence Kemp McKenna, writer and ethnobotanist: born Paonia, Colorado

16 November 1946; married Kathleen Harrison (one son, one daughter;

marriagedissolved 1992); died San Rafael, California 3 April 2000.

use BACK button!